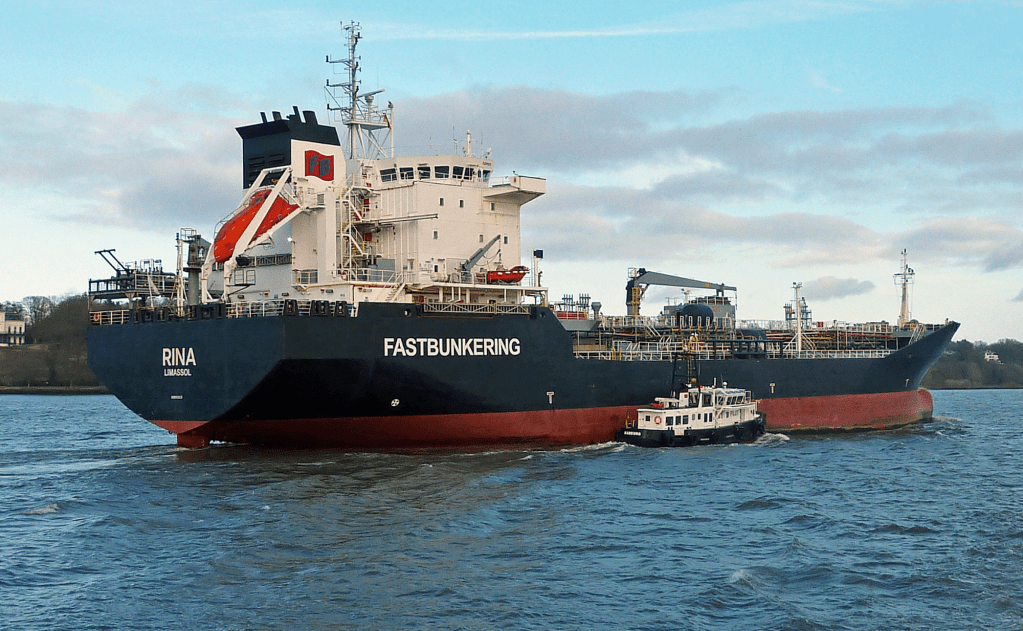

On 8 March, in the grey morning waters near Denmark’s Skagen port, the bunker tanker Rina prepared for another routine job: refuelling ships moving through one of the world’s busiest sea lanes. But among the 200 vessels that pass daily, many belong to Russia’s growing shadow fleet — ageing, uninsured tankers used to secretly transport Russian oil around the world.

n August 2024, in one such instance, the tanker Rainbow met Zircone between Gotland and Latvia while carrying 37,000 tons of refined oil from Russia’s Primorsk port to Brazil. MarineTraffic data show the ship-to-ship transfer lasted from 13:39 to 16:40.

A similar operation took place in n December 2024, when Rina refuelled Rainbow en route from Primorsk to Libya.

That morning, Rina serviced one of them: Blue, a 20-year-old crude carrier capable of hauling one million barrels of oil. Despite sailing under the flag of Antigua and Barbuda, Blue routinely disables its AIS tracking system and has previously been caught transferring Russian oil to sanctioned ships. After refuelling, it continued towards Primorsk to load oil bound for India.

Rina is owned by FB Trade, a Dubai-registered company closely linked to the Baltic bunkering giant Fast Bunkering, which until recently operated in Lithuania’s port of Klaipėda. Along with its sister ship Zircone, Rina completed 286 ship-to-ship transfers between June 2024 and March 2025, supplying 177 tankers — 159 of which had just visited Russian ports.

Experts say at least 20 of those tankers show clear signs of belonging to the Russian shadow fleet: no insurance from IG P&I Clubs, opaque ownership, and frequent AIS blackouts.

Despite strict EU rules on bunkering vessels carrying Russian oil, Rina and Zircone repeatedly serviced high-risk ships — including the notorious tanker Fotuo, later sanctioned by the EU and UK.

A Baltic Oil Empire in the Grey Zone

Behind these operations stands a network built by Estonian businessman Aleksei Tšulets, founder of Fast Bunkering. For decades his companies dominated the bunkering market in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, often using offshore structures to obscure ownership.

Fast Bunkering has previously been accused of:

re-exporting Belarusian oil products using falsified documents, disguising Russian fuel as Kazakh after the EU embargo, and supplying Russian-origin fuel in Klaipėda via a network of shell firms.

In 2023, Estonian authorities raided Fast Bunkering companies on suspicion of sanctions evasion. Meanwhile, its Lithuanian subsidiary Saurix Kuras purchased more than €30m worth of fuel from Fast Bunkering’s Estonian branch — allegedly Russian oil with falsified certificates.

Sold — But Not Really

Under EU rules, selling tankers requires strict checks to avoid them falling into the shadow fleet. Fast Bunkering says it sold Rina and Zircone to a Latvian firm, but the buyer turned out to be run by Fast Bunkering’s own employees. Months later, the ships were “sold” again to FB Trade in Dubai — a company registered by a former Fast Bunkering specialist and using the same logo.

Even after the transfer, both tankers continue to display the Fast Bunkering brand. Their operations are still promoted on the company’s social channels.

Experts say such ownership changes and front companies are classic red flags for sanctions evasion.

Regulators Struggle, Shadow Fleet Thrives

Governments are aware: Canada and Ukraine have sanctioned Fast Bunkering-linked entities. Yet Rina and Zircone continue fuelling Russia-linked tankers across Danish waters with no interruption.

According to S&P Global, more than 3,100 refuelling operations involving shadow fleet ships occurred in European waters in the year before April 2024.

Sanctions experts warn the system is failing.

“Instead of making the seas safer, the sanctions have created an even more dangerous dark fleet,” says maritime analyst Michelle Wiese Bockmann.

As long as bunkering companies in EU waters continue operating in this legal grey zone, Russia’s shadow fleet — and the profits behind it — will keep expanding.